Diario Perfil June 27, 2010

Lost laughter

Florencia Blanco (Montpellier, Francia, 1971) spent part of her childhood and adolescence in Salta, a region which has taken center-stage in many of her shows. This exhibition, open until July 3 in the Rojas Cultural Center, is the result of such a project, where anonymous hand-tinted antique portraits take on a new life.

By Daniel Molina

When we look at a photo taken when we were children, we recognize the memories of that time, the ever-changing narrative which we relate in our present: but what has become of the child within? The photo is one of destruction, for each time our gestures and features are recorded for posterity; they become a sign of what has been lost for ever. Perhaps this is why it is so hard to look a portrait in the eyes.

The photos exhibited by Florencia Blanco take this experience to a new level, for here she is portraying portraits themselves.

Florencia Blanco was born in France but spent much of her childhood and youth in Salta. She has been showing her photographs since 1997 and has worked (stills, casing or direction assistance) on various films, including two made by her friend Lucrecia Martel: La cienaga and La niña santa. There is indeed something of the new Argentine filmmaking style in Blanco’s photographic approach; although she is not caught up in the picturesque elements of local color nor in the denunciation of poverty, she nonetheless manages to persuade the spectator to question himself about such things and much more.

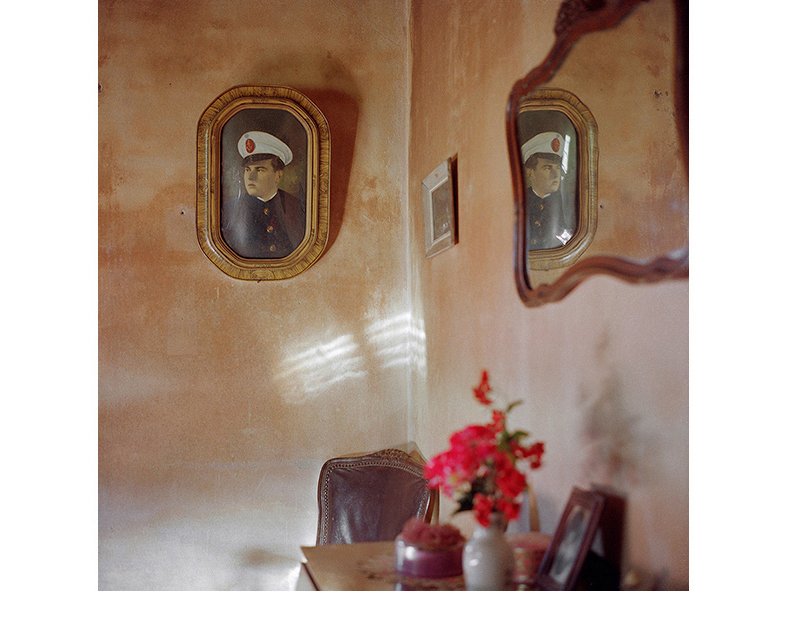

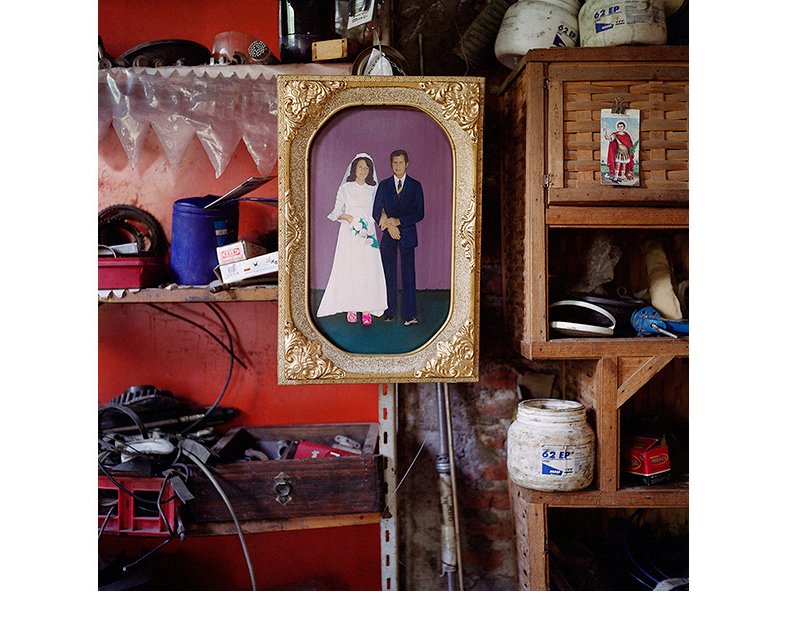

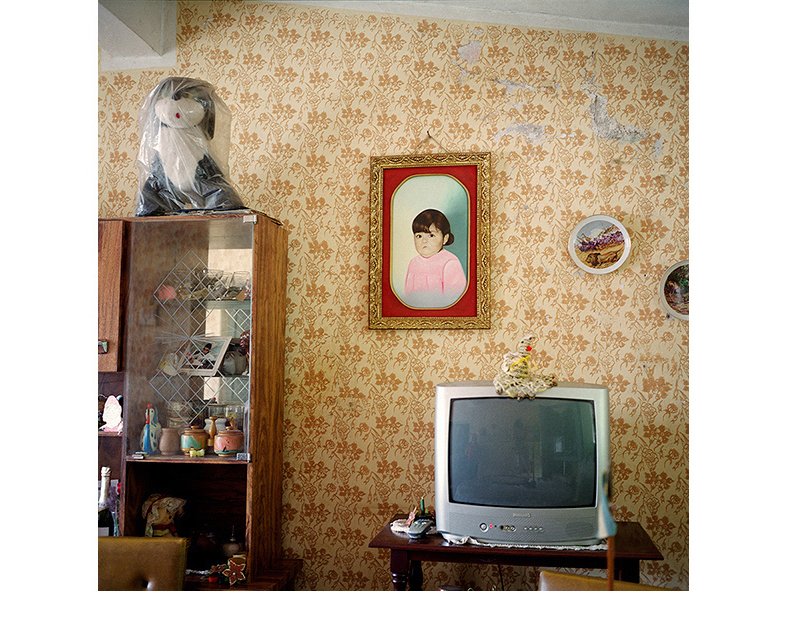

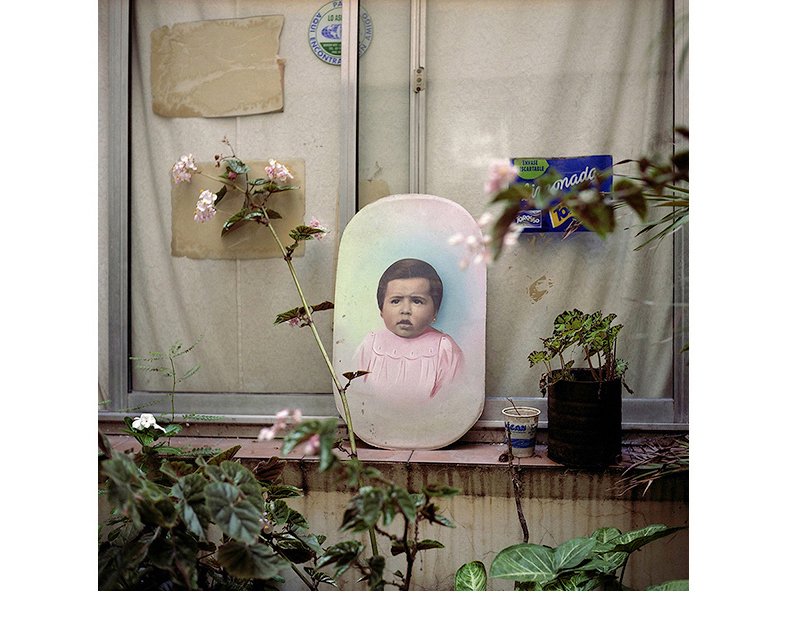

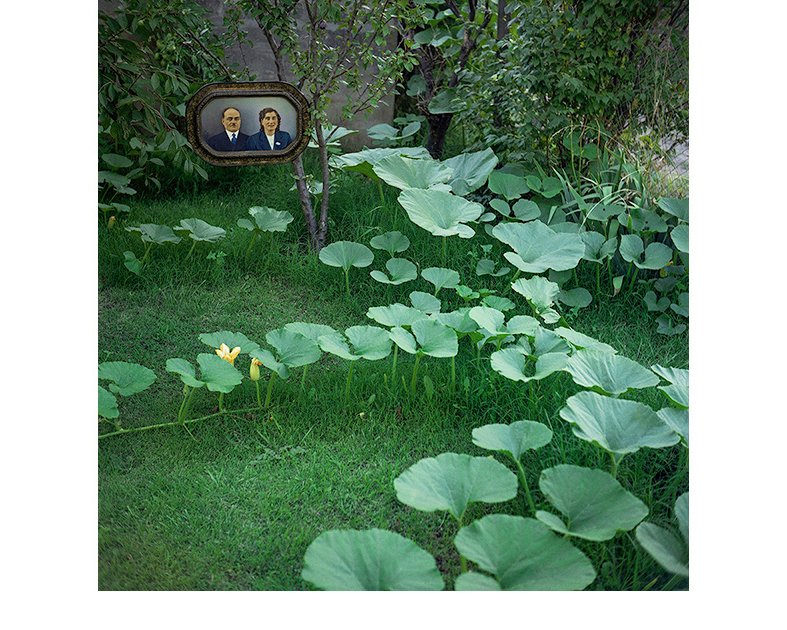

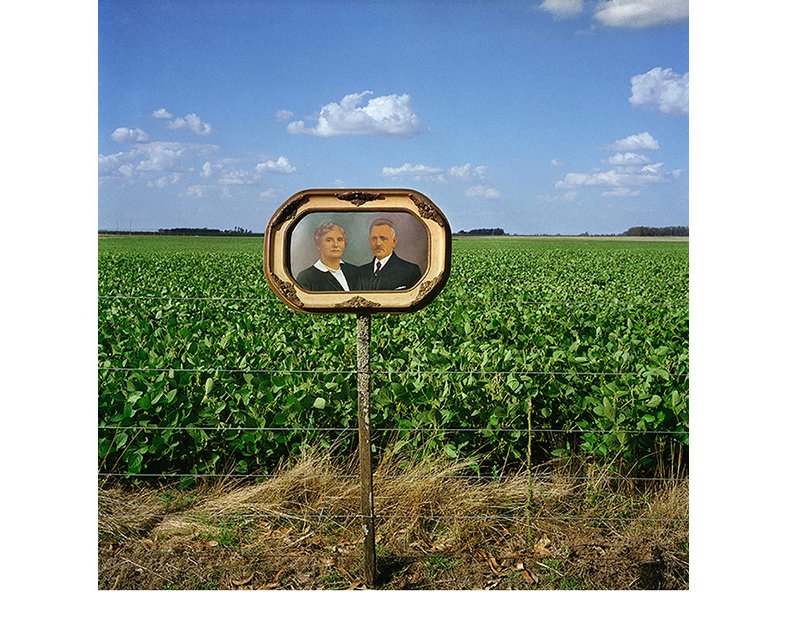

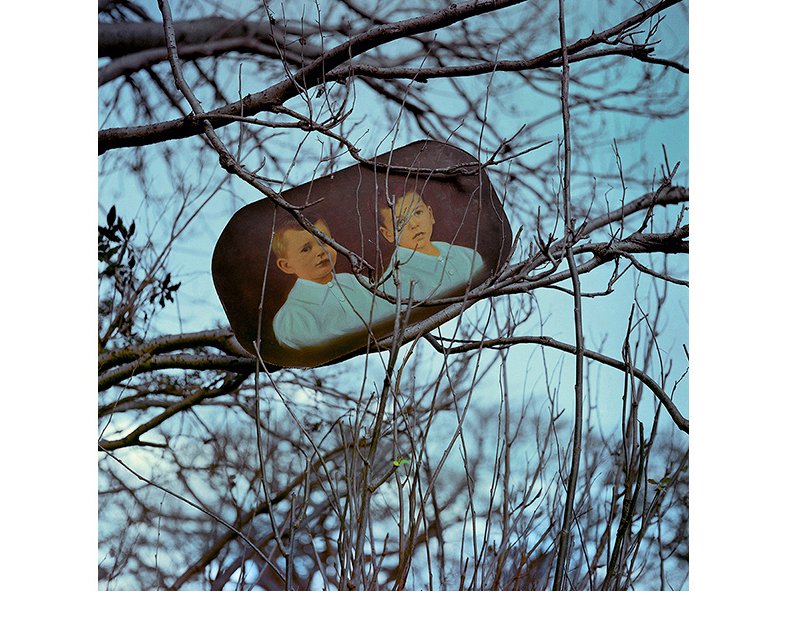

Oil photographs had their moment of glory in Latin America over more than half a century ago. The photographers who used to work with this technique blew up small portraits belonging to their clients and then used water color washes to delicately tint their features. For clothes and the background elements they used thicker paint. Thus, the small photographs which a family might keep in the back of a drawer became the first large pictures to hang in their homes.

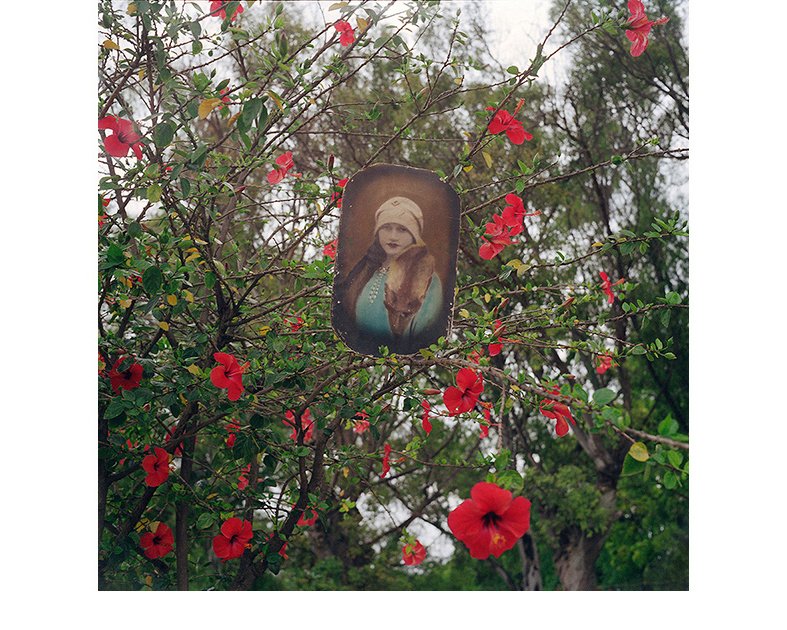

In the series Salteños, the artist’s abiding interest in all things mortal was evident. Everything shown belonged to a time gone by, or to one already dissolving into the past. In Fotos al oleo, this sense of nostalgia is much stronger. Perhaps this is due—more than to the faded pathos of these antique photos Blanco collected—to the landscapes in which she places them. At the outset, she made various attempts to portray them in their original location, hanging on the wall of the living room or of a family bedroom. But it was only when she removed them from their “natural” context and put them outside, in a cemetery, field or garden, that these oil photographs acquired a new lease of life.

Framed by a field, lying on the overturned earth of an open grave, these anonymous old portraits, painted by craftsmen who are most probably dead too, seem to breathe anew. They are no longer sheltered by the surroundings of musty family homes which blinded them in plain view by transforming them into mere wall decorations. In the light of day, on open ground or among the foliage of a well-tended garden, the frozen smiles of these strangers appear to ask us questions. Who are these people? Why do they all share the same sense of family? Is this similarity real or is it simply born of the distance with which we look at these pictures? What stories did they have to tell? Were they moved by desires such as those which move us? Will we, like them, leave nothing behind except a lost smile hovering above the damp earth of a field?

Photography was thought of in one way as a response to death, the record of a vital instant which was spirited away from destruction. The oil photographs which Florencia Blanco shows us cast doubts on this optimistic attitude. From the moment when our portrait was taken, the image is our farewell.

Daniel Molina 2010